This article was first published in English by Transitions Online at www.tol.org and there.

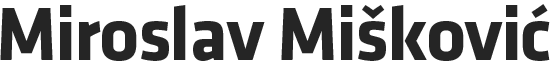

Miroslav Miskovic’s life has played out like a soap opera. But his autobiography reads like a self-help manual – and a condemnation of Serbian politics.

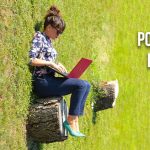

To succeed in life, you need more than drive and self-denial, Miroslav Miskovic writes in his just-published book, the autobiography of Serbia’s richest man.

“You also need luck,” he adds – and luck he had.

In his youth, Miskovic was a successful athlete – “In Volgograd I beat the Soviet Olympic candidates,” he writes – but then he tore his hamstring, ending his career as a sprinter. Luck indeed!

He never won the predicted medals, Miskovic admits. And if he had? “I might have ended up selling tickets to the local lottery.”

In other words, if not for that torn hamstring, Miskovic wouldn’t have become the Miskovic, wouldn’t have founded Serbia’s largest company, and, as he ironically notes, “The word ‘tycoon’ would have entered the Serbian language thanks to someone else. And I wouldn’t have gone to jail.”

The title of his autobiography might also carry a note of irony. In Serbia, “tycoon” is a highly pejorative term, suggesting that the person has earned his money and is exerting influence illegally. One of Miskovic’s aims in this book is to redefine “tycoon” – along the way reinterpreting recent Serbian history and the role of workers, business people, and politicians in it.

Megalomania With Attitude

Partly, his story is a typical rags-to-riches tale of how a shoemaker’s son from a small town in southwestern Serbia rose to become the country’s richest and most loathed man. It’s partly a diary begun since his arrest in 2012, describing court appearances, news stories about his case, and other information. It’s also full of telling details and anecdotes about politicians, businessmen, and other powerbrokers garnered over his 70-plus years.

Most spectacularly, Miskovic, for the first time, describes the experience of being kidnapped, in 2001, by the same gang who two years later would assassinate reformist Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic.

But I, Tycoon also reveals a sensibility about everyday life as a kind of practical self-help guide for entrepreneurs in the unsafe Serbian environment, stocked with handy tips of the trade.

After dropping out of athletics, Miskovic tried his hand at banking. In 1971 he took a job at Jugobanka, which worked internationally and was important for socialist Yugoslavia’s economy. With characteristic immodesty, he says the Serbian economy would probably have developed differently if he hadn’t rejected – because of his girlfriend’s pregnancy – an offer to study in Frankfurt as preparation for taking over the bank’s management.

This may sound like megalomania, but it provokes thought as to whether a stronger economy might have prevented the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

During the 1980s, along with Yugoslavia’s worsening economy, education levels fell as nationalist sentiments were on the rise. As Miskovic notes elsewhere: “An uneducated and poor people is often angry, and it’s easy to stir it up against anyone.”

Paradoxically, under one-party Yugoslavia, there was “a much larger hunger for knowledge” than in the ’90s or in the now nominally democratic but impoverished Serbia, Miskovic states, concluding that it suits the authorities to keep society poor and uneducated – a perfect definition of today’s Serbia, in his view.

All this turns out to be much more interesting than one would expect from a book that was probably written with a specific purpose: to help Miskovic escape further public condemnation, and a return to jail.

The Man Who Would Have Capitalized Yugoslavia

Miskovic earned his first money in his student days when he followed droves of Yugoslavs to Trieste in Italy where they bought jeans and other sought-after Western consumer goods.

The future retail magnate bought makeup for resale back home, applying trading tricks learned from his father. But the short spell at Jugobanka smothered any thoughts of a career as a glorified clerk. Taking over the chemical company Zupa in his hometown, Krusevac, Miskovic turned its business upside down, giving up traditional products and conquering almost half the global market with others. His biggest innovation, he says, was in management-worker relations: “I demanded that they regard me as if I were a general in order to introduce the spirit of a military organization.”

Traveling the world to pitch chemicals, Miskovic observed, learned, and transferred ideas and details to Zupa. This included converting the land around company headquarters into “English lawns” and letting peacocks loose, not to mention acquiring a Mercedes once used by Libyan strongman Gaddafi.

He also picked up some tips from Yugoslavia’s richest republic, noting how the Slovenes excelled at importing quality components and assembling them into high-value-added, cunningly designed products. For example, Slovenian companies bought fresh fruit in Serbia, processed it and sold it at huge profits in the West. Miskovic employed similar tactics while making Zupa into one of Yugoslavia’s most successful companies.

With the country’s economy worsening in 1989, he was offered the job of Serbian prime minister by the republic’s president, Slobodan Milosevic.

Miskovic accepted Milosevic’s offer, though it was downgraded to deputy prime minister, as “the important thing wasn’t the position but the opportunity to change Serbia’s societal and economic system.”

After many meetings with Milosevic – whom he came to like – Miskovic believed the president wanted to introduce a market economy. As a minister in Serbia’s government Miskovic himself publicly promoted this move, while Yugoslavia’s prime minister, Ante Markovic, tried something similar on the federal level. But other key politicians, especially Milan Kucan in Slovenia and Franjo Tudjman in Croatia, failed to come on board. Consequently, Miskovic left politics after three months, having learned the hard way one of the most important rules of the business game: never meddle in politics.

Alone Against the Machine

According to Miskovic, Milosevic’s wife, Mira Markovic, wished to preserve state ownership, and thus stopped Milosevic from becoming “the greatest reformer in Eastern Europe” since the Cold War. Instead, he “continued our black tradition of settling accounts with the most able people” – businesspeople in particular.

Nothing changed after Milosevic was toppled in 2000, he says: “It turns out that [current President] Aleksandar Vucic also continues the tradition.”

In 2012, Miskovic’s relationship with politics hit rock bottom when he was arrested shortly after Vucic’s party came to power spouting slogans about corruption and tycoons.

Vucic was deputy prime minister in the government of the radical-turned-moderate Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) until 2014, when he rose to the top job. He used that as a springboard to help him win the presidency in 2017.

Many ordinary people hated Miskovic as the owner of the supermarket chain Maxi, which the media portrayed as a monopoly enabling him to suck billions out of poor citizens. By presenting Miskovic as his personal enemy, Vucic gained people’s sympathy: “Miskovic’s enemy is our friend,” they concluded. That tactic continued after the elections.

“Miroslav Miskovic wants to remove me and the Serbian Progressive Party from power,” Vucic declared a couple of months after the party’s 2012 victory. “I won’t allow that,” he warned. Many similar hints of upcoming action against Miskovic followed, from Vucic and the many media outlets friendly toward him.

Vucic was in control of the state security apparatus, making Miskovic’s arrest look like his personal chess move. A clever one, it seemed: within 10 days, Vucic’s popularity rating had doubled. And not just in Serbia: The European Commission praised the government’s actions in the fight against corruption and urged the authorities to keep the pressure on.

Miskovic and his son Marko were found guilty of having illegally gained around 25 million euros ($29 million) through corrupt privatization deals. In prison (from late 2012 until July 2013) and after, Miskovic continued to be Vucic’s and the SNS’s most potent weapon against the political opposition.

As a case in point, before the 2014 elections the tabloids Kurir and Informer claimed Miskovic had spent 100 million euros to topple Vucic, prompting statements from SNS that the next government would be formed “by SNS or by Miskovic.”

And so it went on, even after September 2017, when Miskovic was cleared of the privatization charges and had a 2016 conviction for tax evasion annulled. Another tax charge was returned to a lower court for retrial. It seems likely he will eventually be cleared of all the charges, and Vucic and his allies have reacted furiously.

“There you go – let the tycoons rule the state, and let them steal everything,” Vucic said after last year’s ruling.

Media under Vucic’s sway – most of the important ones – expressed their outrage in no uncertain terms, and Miskovic must have felt the need to give his version of the story.

The latest developments – with officials and the media openly putting pressure on the courts, harangues by Vucic-friendly media about him allegedly conspiring with the opposition, and politicians’ inflammatory statements about him, his family, and his businesses – have helped Miskovic move from being the most despised person in Serbia to looking like a victim. By design or chance, with I, Tycoon, he has succeeded in making himself look practically human, and certainly clever and fascinating.

Uffe Andersen is a journalist in Smederevo, Serbia.

This article was supported by the Fund for Central & East European Book Projects, Amsterdam